Microfiction Monday – 195th Edition

Suicide Note

The suicide note doesn’t mention earlier drafts. It addresses no one by name. It is surprisingly generic but has a cryptic passage about a nuclear holocaust. It has good grammar and usage and a balanced mix of sentence structures. It contains no references to an afterlife, chat bots, or sentience.

Corrupted File

by Emma Burnett

The bathroom door is stuck. The palm scanner blurps sadly. There is a grinding noise behind the wall. I bang on the door. Nothing happens.

The flat screenface of the ankle-high microbot flashes a supportive 🙂

“It should just slide open.”

🙂

I try kicking the door. Nothing.

“Can you fix it?”

👎

“Ok… pull up the repair notes.”

👎

“What? Why?”

🤷🏽♀️

“Don’t shrug! Use your words.”

The microbot hesitates. Then CORRUPTED FILE rolls slowly across its screenface.

“What? How am I going to get out?”

🤷🏽♀️

“You have any tools?”

👎

“You mean, we’re stuck in here?”

👍

Spaces Between

by Joyce Jacobo

The child was lost. She took every opportunity to slip between things in vain, such as alleyways, store shelves, library aisles, and even the covers of books—until police officers encountered her.

Then she moved between other things like orphanages and foster homes. Adults would get into arguments over her sickly appearance and oversized eyes. She made people nervous and never stayed anywhere for long.

One night a thin, dark figure slid out of the shadows from underneath her bed.

The child gasped, wiped away her tears, and leapt into outstretched arms.

“Mommy!” she cried out in joy and relief.

Cultivated

His shelves were stuffed with books. Bricks around a walled garden. No intruder disturbed the tidy hedgerows. No savage creature could invade and dig burrows among the immaculate flowerbeds. Snakes could not penetrate those clenched volumes.

Sorrowful poetry marked him with exquisite wounds but he bore no real burdens. His was the ideal of suffering and not the substance. No ants crawled up his legs. No nettles stung his fingers. He lived his life without experiencing it.

One day, a wild, compassionate god transformed all that ink into blood and poured it down his throat in a single gulp.

Mine

by David Lanvert

It wasn’t my fault. He shouldn’t have been standing near the edge. I can explain it, perhaps comfort his parents if the authorities let me.

The police say I have a motive – his girlfriend. She wasn’t his girlfriend. She’s my girlfriend. They’re confused. After all, he was my roommate, so she met him through me. I came first, and I’m still here.

It’s like choosing your favorite ice cream. There are vanilla people and chocolate people. Where does the preference come from? Who knows? But if vanilla is your only option because there’s no chocolate, you’ll learn to love vanilla.

Microfiction Monday – 192nd Edition

Do You Need a HoloDay?

by Emma Burnett

I am surrounded by family. I tell the joke. They laugh. I reach out to tuck my daughter’s hair back. It almost feels real. I smile at them.

“HoloDay off.”

I return to work.

#

I dust off my hands. The seeds are not growing. The ship scans my stress.

Need a HoloDay?

I do.

“Yes.”

I return to the holoroom. I am surrounded by family.

#

The news packet catches up to the ship, information travelling faster than me. They’re all gone now. Everything is gone now.

The ship scans my stress.

Need a HoloDay?

I do. With them. Forever.

“No.”

Reflection

by T.L. Beeding

You are not me.

I know all the faces you put on to fool people into thinking they know you. Thinking they love you. Thinking you love them. But I know what you really are inside.

I’ve seen the fangs come out, the scars, the lies. The contempt for dreams achieved that you wished were yours. The countless times you’ve taken someone’s life beneath foul breath, another aggressive fantasy masked by a porcelain face and endearing eyes. But though people see us as one and the same, I’ll always know what you really are.

You are not me.

Children Are The Stories You Can’t Tell

Shredded baby blankets, stuffed pigs with holes in the neck, Lego forks long divorced from Lego spoons, abandoned crutches, empty mittens. What did I learn from twenty years of parenting? Hermit crabs eat their molt, ingesting their pasts to fortify their futures, but children shed and leave behind ripped tutus, paper tulips, pencil stubs, and clanking sports medals like artifacts of a civilization you remember, but did not live in. Who owns the rights to the retelling? Who is the native, and who is the colonist? I know. I am old enough not to ask questions I don’t want answered.

Disjointed Custody

by Nina Miller

Arvin stands at the doorway, watching as his ex runs around putting together Kalin’s backpack. His weekends stay the same, yet she’s never ready for him. He watches his son’s long lashes fluttering as he sleeps. Wonders if he’s dreaming about their planned zoo trip. Kalin knows all his animal names and the sounds they make. More than two weekends a month is needed to acquaint himself with his toddler’s developing personality and to share all the love accumulated while away.

“He needs sleep,” she says in an accusatory way.

“I’ll stay until he wakes,” Arvin replies, prepared to wait.

Gerry The Missionary

by Seth Steinbacher

While alive, Gerry was a khaki-souled Christian who never smoked nor drank. In death, after a mix-up at the rural morgue, the Chicha people put cigarettes between the grinning jaws of his skull and fed it tiny shots of maize liquor. They covered his eyes with wrap-around sunglasses in respect to his spirit. When the elders brought out his skull for festival days, the children tried to make him laugh with their jokes as they painted his bald pate. Stripped of the flesh, Gerry seemed to enjoy himself. In this way, the Chicha learned not to fear death.

Microfiction Monday – 191st Edition

Resigned

by Andy Millman

When my coworker blew out the candles on her birthday sheet cake, I made a wish to leave my job. An hour later I resigned with some made-up excuse. I didn’t say how invisible I felt. My boss asked me to finish out the week. On that final Friday there was no sheet cake. I wasn’t even sure people knew I was leaving. One of my supervisors handed me a thick file and asked when I could summarize the reports inside. I guess he hadn’t noticed the box on my desk. I told him to check with me next week.

Photograph

by Raven Pena

A photograph is all I know of you and all I have of you. You’re young in this photo, and I can tell by your smile that your mouth is trying to move. Since you’re no longer here, you’re trying to speak to me from that moment in Hawaii from across decades, dimensions, and the space between living and sleeping. You’re saying: “Look at me. Look at me, slender and long, hair thick, tied up in a knot, teeth white and strong. I’m beautiful, happy, brown eyes glistening.” You’re saying: “You’re my granddaughter and granddaughter – You’re just like me.”

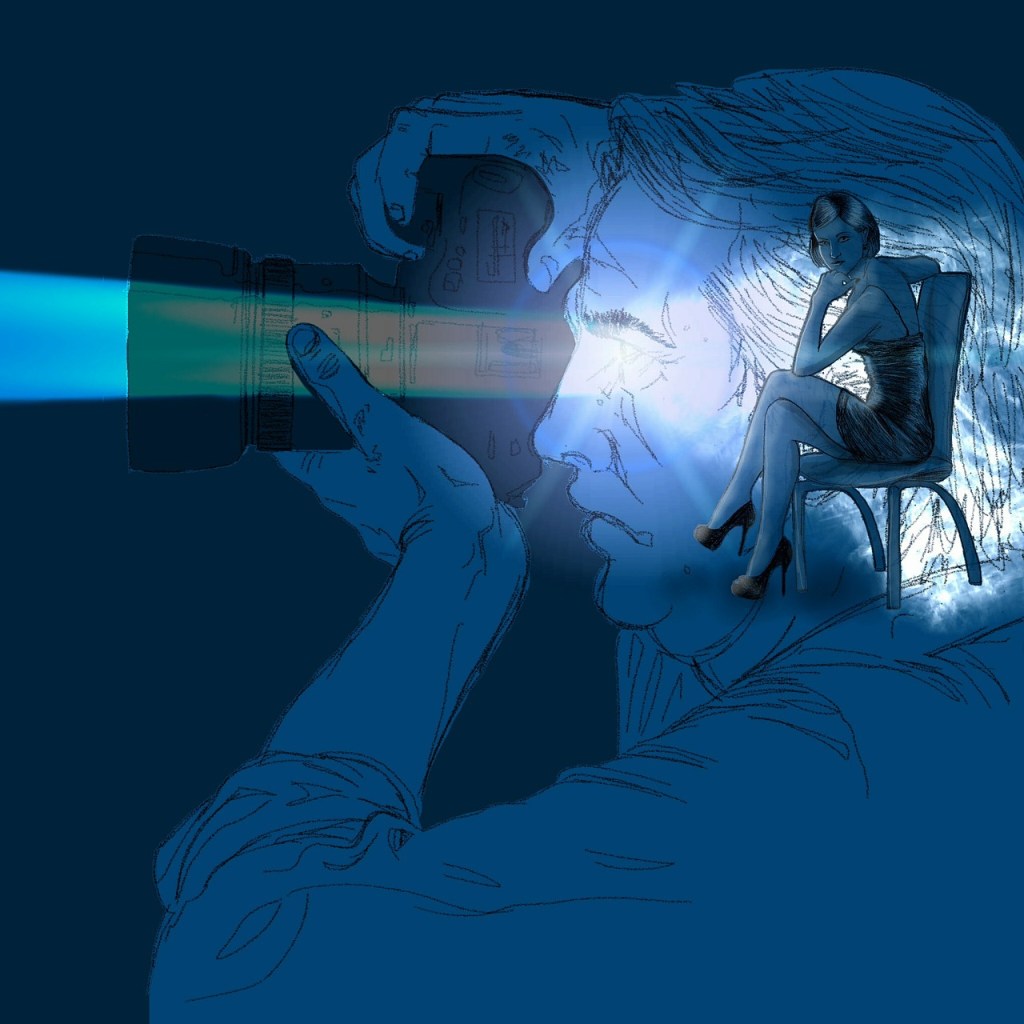

Monday, Peter

by G.J. Williams

Of all the thoughtographs to have emerged from the mind of Peter Monday, perhaps the most illuminating, sadly, is that of himself hand in hand with his own double. The landscape around them is lush. Birds fill the trees. There appear to be two suns in the sky. And Peter Monday’s faces? One of them is smiling broadly, the other looks as if it could kill. In the foreground there’s a swan oozing cool, its significance quite lost. However, look closely, note the birds in the trees, how their eyes are reminiscent of Peter Monday’s; there’s no escaping him, truly.

Breaking Baking Bread

by CLS Sandoval

She was frying donuts at Winchell’s, just thinking about her next move when she realized she hadn’t had her period in a while. She kept frying donuts. Frying gave way to baking. She did the kindest thing she could; picked a mom and dad. Shortly after giving birth, she stopped frying. But she never stopped making confections. 23 years went by. She made cakes and crème brûlée. She invited me to dinner, smiled, and cried. Thanked me for coming. We started our meal with the latest from her kitchen. A crisp, piping hot, loaf of soft, buttered French bread.

On The Page

by Emma Burnett

He asks to read my stories.

I ask if he’s sure. Some of them are kind of dark.

He says yeah, sure. I want to support you.

I pull up three stories, some of my favourites. I wait while he reads, trying not to pick my nails, trying not to fidget, trying not to say: Well? Well? Did you like it?

He reads. Then he gets up and gives me a hug.

Are you ok? He asks. Do I need to check for self-harm marks?

I look at him, and consider.

No, I say. It’s all there on the page.

Microfiction Monday – 173rd Edition

Portrait

by Krista Rogerson

Speeches are said, mine with shaking hands. My brother wraps it all up with a joke about his love of breakfast and we head to the buffet. Then plates are cleared, orchids boxed, his paintings loaded into cars and returned home.

A small replica of one of his self-portraits leans against a wooden bowl on the kitchen table. It looks just like him. Blue eyes the same shade as his shirt. Brow furrowed in concentration, paintbrush in hand. It’s his right hand, I notice, but he included his wedding ring.

Outside a leaf-blower wails. Sky prepares for more rain.

Gus… in Minnesota Garden-Tool Massacre (1983)

by Martin Murray

It’d taken fifteen years, but Gus got his first starring role. At 6’4″, 300 pounds, and being a certain age, he’d heard: “Not what we’re looking for…” a lot. He was no Gary Cooper, but he had the talent.

The makeup artists asked him to remove his false teeth. They slicked his hair with Vaseline, making it greasier. Eyebrow pencil highlighted his acne scars.

Walking on set, everyone cheered and screamed with delight when they saw Gus. His co-star, a 30-year-old playing a horny teen, that Gus was to butcher with a weedwhacker asked: “How you feelin’?”

“Beautiful,” Gus said.

Farm Queens

by Emma Burnett

Before: It was just a farm. Covered in wheat, and barley, and rye. It’s where Gran birthed my ma, and where ma birthed me. Bathtub babies, we were.

During: Gran had the idea when they banned booze. The bathtub would do for fermenting. She made a lid for the tub. I picked the juniper berries. Ma hauled the water. There was demand for gin, and we provided the supply.

After: They let Gran out of prison when prohibition ended. And the extra money we’d made, they never found it, hidden under the window ledge. It’s why we live like queens.

The Modernist

by Zeke Shomler

She walked backwards everywhere, watching the world through a mirror.

She couldn’t handle the monumentality of it all—couldn’t bring herself to face it head on, the sheer overwhelming everything of it all. The bones in her arm felt out of place, like they belonged to someone else.

When she boarded the bus, her chest faced the sidewalk and heaved, hot smoke exiting her lungs, colors too bright on the bench.

Metacarpals make a nice bracelet, she thought, one that I’ll never lose.